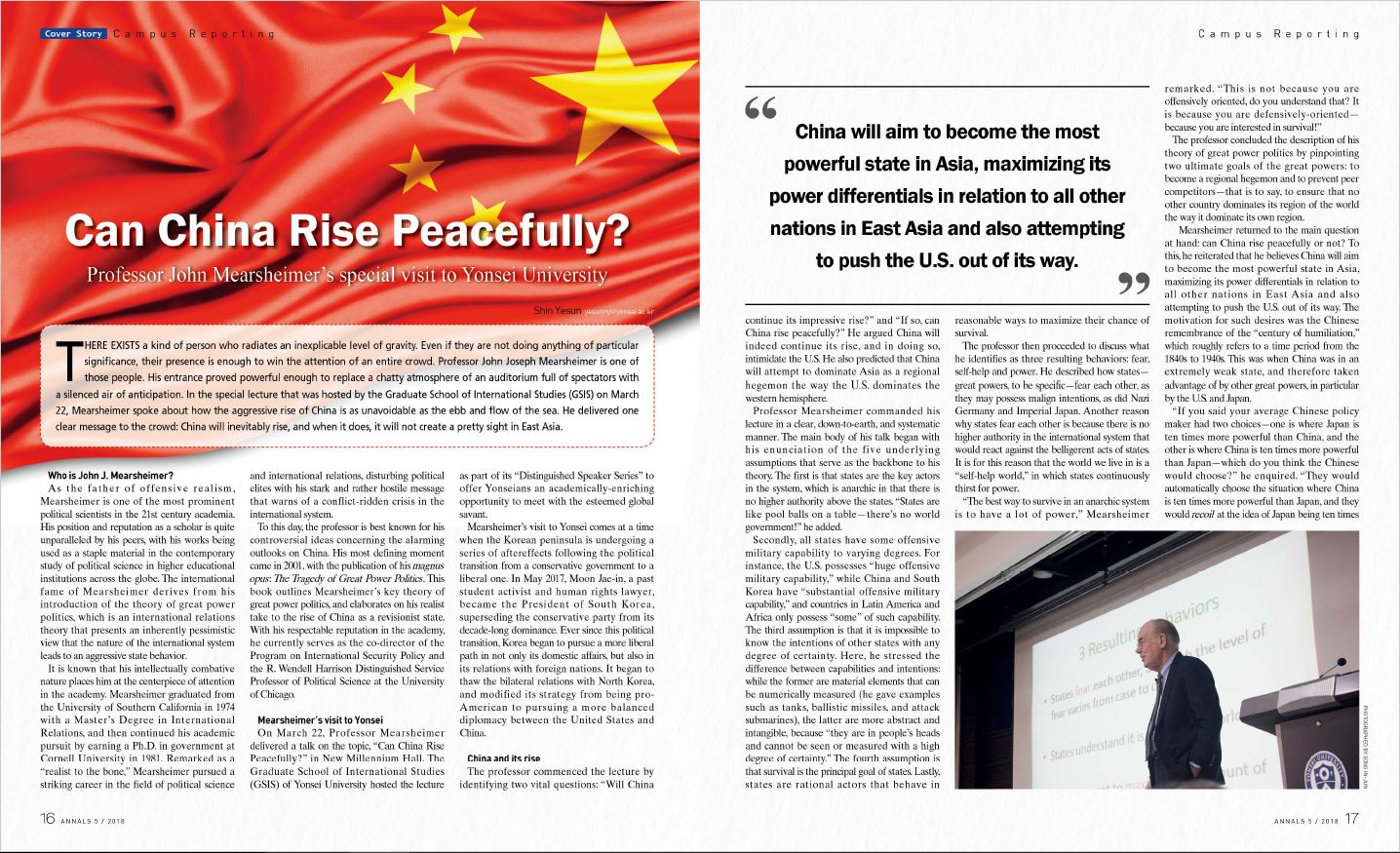

THERE EXISTS a kind of person who radiates an inexplicable level of gravity. Even if they are not doing anything of particular significance, their presence is enough to win the attention of an entire crowd. Professor John Joseph Mearsheimer is one of those people. His entrance proved powerful enough to replace a chatty atmosphere of an auditorium full of spectators with a silenced air of anticipation. In the special lecture that was hosted by the Graduate School of International Studies (GSIS) on March 22, Mearsheimer spoke about how the aggressive rise of China is as unavoidable as the ebb and flow of the sea. He delivered one clear message to the crowd: China will inevitably rise, and when it does, it will not create a pretty sight in East Asia.

Who is John J. Mearsheimer?

As the father of offensive realism, Mearsheimer is one of the most prominent political scientists in the 21st century academia. His position and reputation as a scholar is quite unparalleled by his peers, with his works being used as a staple material in the contemporary study of political science in higher educational institutions across the globe. The international fame of Mearsheimer derives from his introduction of the theory of great power politics, which is an international relations theory that presents an inherently pessimistic view that the nature of the international system leads to an aggressive state behavior.

It is known that his intellectually combative nature places him at the centerpiece of attention in the academy. Mearsheimer graduated from the University of Southern California in 1974 with a Master’s Degree in International Relations, and then continued his academic pursuit by earning a Ph.D. in government at Cornell University in 1981. Remarked as a “realist to the bone,” Mearsheimer pursued a striking career in the field of political science and international relations, disturbing political elites with his stark and rather hostile message that warns of a conflict-ridden crisis in the international system.

To this day, the professor is best known for his controversial ideas concerning the alarming outlooks on China. His most defining moment came in 2001, with the publication of his magnus opus: The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. This book outlines Mearsheimer’s key theory of great power politics, and elaborates on his realist take to the rise of China as a revisionist state. With his respectable reputation in the academy, he currently serves as the co-director of the Program on International Security Policy and the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago.

Mearsheimer’s visit to Yonsei

On March 22, Professor Mearsheimer delivered a talk on the topic, “Can China Rise Peacefully?” in New Millennium Hall. The Graduate School of International Studies (GSIS) of Yonsei University hosted the lecture as part of its “Distinguished Speaker Series” to offer Yonseians an academically-enriching opportunity to meet with the esteemed global savant.

Mearsheimer’s visit to Yonsei comes at a time when the Korean peninsula is undergoing a series of aftereffects following the political transition from a conservative government to a liberal one. In May 2017, Moon Jae-in, a past student activist and human rights lawyer, became the President of South Korea, superseding the conservative party from its decade-long dominance. Ever since this political transition, Korea began to pursue a more liberal path in not only its domestic affairs, but also in its relations with foreign nations. It began to thaw the bilateral relations with North Korea, and modified its strategy from being pro-American to pursuing a more balanced diplomacy between the United States and China.

China and its rise

The professor commenced the lecture by identifying two vital questions: “Will China continue its impressive rise?” and “If so, can China rise peacefully?” He argued China will indeed continue its rise, and in doing so, intimidate the U.S. He also predicted that China will attempt to dominate Asia as a regional hegemon the way the U.S. dominates the western hemisphere.

Professor Mearsheimer commanded his lecture in a clear, down-to-earth, and systematic manner. The main body of his talk began with his enunciation of the five underlying assumptions that serve as the backbone to his theory. The first is that states are the key actors in the system, which is anarchic in that there is no higher authority above the states. “States are like pool balls on a table—there’s no world government!” he added.

Secondly, all states have some offensive military capability to varying degrees. For instance, the U.S. possesses “huge offensive military capability,” while China and South Korea have “substantial offensive military capability,” and countries in Latin America and Africa only possess “some” of such capability. The third assumption is that it is impossible to know the intentions of other states with any degree of certainty. Here, he stressed the difference between capabilities and intentions: while the former are material elements that can be numerically measured (he gave examples such as tanks, ballistic missiles, and attack submarines), the latter are more abstract and intangible, because “they are in people’s heads and cannot be seen or measured with a high degree of certainty.” The fourth assumption is that survival is the principal goal of states. Lastly, states are rational actors that behave in reasonable ways to maximize their chance of survival.

The professor then proceeded to discuss what he identifies as three resulting behaviors: fear, self-help and power. He described how states—great powers, to be specific—fear each other, as they may possess malign intentions, as did Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Another reason why states fear each other is because there is no higher authority in the international system that would react against the belligerent acts of states. It is for this reason that the world we live in is a “self-help world,” in which states continuously thirst for power.

“The best way to survive in an anarchic system is to have a lot of power,” Mearsheimer remarked. “This is not because you are offensively oriented, do you understand that? It is because you are defensively-oriented—because you are interested in survival!”

The professor concluded the description of his theory of great power politics by pinpointing two ultimate goals of the great powers: to become a regional hegemon and to prevent peer competitors—that is to say, to ensure that no other country dominates its region of the world the way it dominate its own region.

Mearsheimer returned to the main question at hand: can China rise peacefully or not? To this, he reiterated that he believes China will aim to become the most powerful state in Asia, maximizing its power differentials in relation to all other nations in East Asia and also attempting to push the U.S. out of its way. The motivation for such desires was the Chinese remembrance of the “century of humiliation,” which roughly refers to a time period from the 1840s to 1940s. This was when China was in an extremely weak state, and therefore taken advantage of by other great powers, in particular by the U.S. and Japan.

“If you said your average Chinese policy maker had two choices—one is where Japan is ten times more powerful than China, and the other is where China is ten times more powerful than Japan—which do you think the Chinese would choose?” he enquired. “They would automatically choose the situation where China is ten times more powerful than Japan, and they would recoil at the idea of Japan being ten times more powerful than China,” he added. To this, a number of spectators gave reactions of obvious disappointment. During the question and answer session, one student posed the possibility of a peaceful democratization of China, an idea that was subsequently rejected by Mearsheimer.

Moreover, he also predicted that China is likely to interfere in the politics of the Western hemisphere the way the U.S. has been interfering in Asia’s politics. To support such a prediction, Mearsheimer offered the Chinese involvement in Africa and the increasingly close relations between China and countries in the Middle East as the evidence. In response to such Chinese action, he further projected that the U.S. is likely to go to great lengths to prevent the domination of China over Asia, as his theory and historical records suggest. He believes that this is the reason behind the American “pivot to Asia*,” which is seen to have the containment of Chinese power at its core. Mearsheimer sees the pivot to Asia as the beginning of many more checks and controls to come from the U.S. in retaliation to the rise of China as a peer competitor.

“What about China’s neighbors?” questioned Mearsheimer, redirecting the course of the lecture to address the reactions of the countries of East Asia. “I believe almost all of China’s neighbors are likely to ally with the U.S. to form a balancing coalition against China.”

He explained that with the minor exceptions of North Korea, Pakistan, Laos, and a few more nations, the rest of East Asia—including South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, India, and even Russia—will join the balancing coalition in retribution to the Chinese rise to power. He also provided a rather grim outlook on East Asian security by noting how he believes all of this will lead to an intense security competition in East Asia, which will have the potential to erupt in war.

Implications to Korea

In a closing remark, Mearsheimer expounded the implications of these forecasts for the Korean peninsula. He commented how the rise of China will lead to the tightening of bonds for both Koreas, but in opposite directions; South Korea will join the currently forming American-led balancing coalition against China, while North Korea will become an even stronger ally of China. However, Mearsheimer did add that South Korea, while engaging in a security competition with China, will continue to have significant economic intercourse with China.

The professor acknowledged the economic interdependence theory as “the number one counterargument" that is used against him. This theory argues that the economic intercourse between China, its neighbors, and the U.S. makes it “suicidal for any one of those countries to start a war, because you would be killing the goose that lays the golden eggs.” He said that as a “good realist,” he strongly rejects this theory, and referred to a historical example of Europe around the period of the First World War in proving his logic that economic cooperation does not overpower security competition.

The gray forecast climaxed with Mearsheimer’s statement that “there is virtually no chance that Korea will be unified in the foreseeable future.” This remark evoked a wave of sighs, murmurs and laughter among the crowd. As South Korea forms closer ties with America, and North Korea with China, the professor argued that the Korean peninsula will become one of the four major points of conflict in East Asia, with the other three being the East China Sea, South China Sea, and Taiwan.

In the face of this argument, however, stands the recent thawing of relations between the two Koreas. The North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has been displaying an increasing amount of interest in maintaining closer ties with South Korea in the past months, to which President Moon Jae-in of South Korea has been responding with a high degree of mutual willingness. Although Kim’s intentions remain unclear at the moment, the opening up of North Korea is creating amicable inter-Korean relations in 2018. Such favorable relations were demonstrated on numerous occasions this year, including the march under a unified peninsula flag and the unified Korean women’s hockey team in the PyeongChang Winter Olympics, North Korea’s hosting of a cross-border K-pop performance on April 1 and 3, and the inter-Korea summit that is scheduled to take place in the coming weeks.

Moreover, Mearsheimer forecast the nuclearization of South Korea. He elaborated how it will gain greater incentives to consider the acquirement of its own nuclear deterrent in facing the North Korean provocations. This was another rather sensitive projection that Mearsheimer put forward, with nuclearization being a fiercely contended issue in Korea.

“I think South Korea will flirt with that idea more and more in time,” he explained. In response to this, he noted how the U.S., being an avid opponent of nuclear proliferation, will have to devise a new strategy to extend its nuclear umbrella over South Korea. However, his point concerning the nuclearization of South Korea remains largely obscure, considering the liberal agenda of the Moon administration.

With regards to such complexities that arise from Mearsheimer’s forecast, You GeHeon (Sr., UIC, Dept. of Political Science & Int. Relations), an undergraduate student majoring in political science and international relations, shared his thoughts with The Yonsei Annals. “As one might expect from an offensive realist, Dr. Mearsheimer's prediction for the future of the Korean peninsula was sobering,” You said. He further commented, “the prospect of ROK's potential to go nuclear aligned with its domestic conservative rhetoric.”

The last prediction that Mearsheimer made in the lecture was that it is possible that China will eventually become so powerful that it will be “impossible" to prevent it from achieving hegemony in Asia. He concluded that should China dominate East Asia the way the U.S. dominates the Western hemisphere, South Korea will effectively become a “semi-sovereign state,” which, he argued, is the reason why South Korea will balance with the U.S. against China.

As an ending remark, Professor Mearsheimer shared his thoughts on theory. While reemphasizing that his entire analysis on the rise of China was wholly based on theory, he also highlighted how it is of paramount importance to understand that theories are not always right. Acknowledging that theories are simplifications of reality, he further stated, “My view is that if the theory is right 75% of the time, you get in the hall of fame.”

“What does all this tell you about my presentation?” he questioned the spectators at the end of his talk. “That there is a good chance that I am wrong—25% would be my estimate. Given the depressing stories I told, let’s hope that I am wrong!”

With that ending remark, the floor was passed to the audience for a question and answer session, which continued for about 30 minutes. The questions ranged from inquiries into the specifics of his theory to the role of President Donald Trump, the implications of cyber capabilities of the great powers, and the possibility of the democratization of China.

Following the lecture, the Annals conducted student interviews to discover the opinions of fellow Yonseians regarding Mearsheimer’s talk. An Sohyun (Jr., UIC, Dept. of Culture & Design Management) remarked, “Professor Mearsheimer's lecture was definitely an eye-opening experience—it was concise, easy, yet filled with sharp insight. I could not have asked for a better speaker.”

Some other students, however, were not so impressed with Professor Mearsheimer’s lecture. One particular student majoring in international studies, Kim Yoonjeh (Jr., UIC, Dept. of International Studies), expressed his disappointment with the event. “I was expecting great things, but it was mostly just a repetition of his book. I wish it had been more than just a basic introduction to his theory,” Kim said.

* * *

Will or will not China continue its impressive rise? The question first appeared in the early 1990s with the end of the Cold War, and has been garnering an increasing level of gravity in the circle of academia. The edge of the question is embedded upon the nature of scholastics: one course of action is subject to differing interpretations depending on the school of thought that a scholar follows. In this way, while some view the Chinese growth as an inevitable and irreversible course of action that has the danger to overturn the world order, others view it as a simple and natural phenomenon that is frequently seen in a rising state. One must not overlook the fact that the life’s work and intellectual prowess of Mearsheimer provide only one of many interpretations.

*Pivot to Asia: A strategy that places the central focus of American foreign policy on Asia.