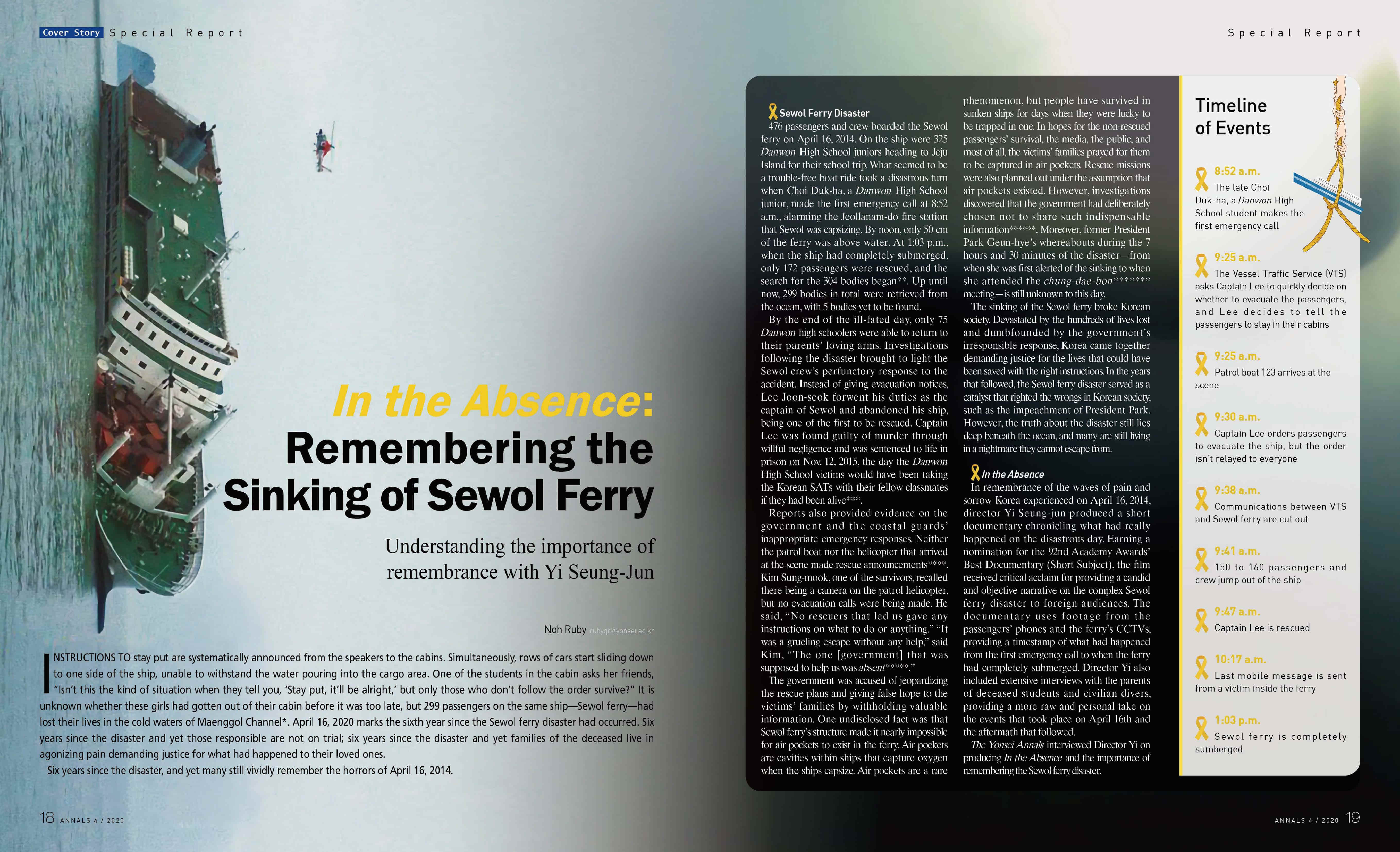

INSTRUCTIONS TO stay put are systematically announced from the speakers to the cabins. Simultaneously, rows of cars start sliding down to one side of the ship, unable to withstand the water pouring into the cargo area. One of the students in the cabin asks her friends, “Isn’t this the kind of situation when they tell you, ‘Stay put, it’ll be alright,’ but only those who don’t follow the order survive?” It is unknown whether these girls had gotten out of their cabin before it was too late, but 299 passengers on the same ship—Sewol ferry—had lost their lives in the cold waters of Maenggol Channel*. April 16, 2020 marks the sixth year since the Sewol ferry disaster had occurred. Six years since the disaster and yet those responsible are not on trial; six years since the disaster and yet families of the deceased live in agonizing pain demanding justice for what had happened to their loved ones.

Six years since the disaster, and yet many still vividly remember the horrors of April 16, 2014.

Sewol Ferry Disaster

476 passengers and crew boarded the Sewol ferry on April 16, 2014. On the ship were 325 Danwon High School juniors heading to Jeju Island for their school trip. What seemed to be a trouble-free boat ride took a disastrous turn when Choi Duk-ha, a Danwon High School junior, made the first emergency call at 8:52 a.m., alarming the Jeollanam-do fire station that Sewol was capsizing. By noon, only 50cm of the ferry was above water. At 1:03 p.m., when the ship had completely submerged, only 172 passengers were rescued, and the search for the 304 bodies began**. Up until now, 299 bodies in total were retrieved from the ocean, with five bodies yet to be found.

By the end of the ill-fated day, only 75 Danwon high schoolers were able to return to their parents’ loving arms. Investigations following the disaster brought to light the Sewol crew’s perfunctory response to the accident. Instead of giving evacuation notices, Lee Joon-seok forwent his duties as the captain of Sewol and abandoned his ship, being one of the first to be rescued. Captain Lee was found guilty of murder through willful negligence and was sentenced to life in prison on November 12, 2015, the day the Danwon High School victims would have been taking the Korean SATs with their fellow classmates if they had been alive***.

Reports also provided evidence on the government and the coastal guards’ inappropriate emergency responses. Neither the patrol boat nor the helicopter that arrived at the scene made rescue announcements****. Kim Sung-mook, one of the survivors, recalled there being a camera on the patrol helicopter, but no evacuation calls were being made. He said, “No rescuers that led us gave any instructions on what to do or anything.” “It was a grueling escape without any help,” Kim said. “The one [government] that was supposed to help us was absent*****.”

The government was accused of jeopardizing the rescue plans and giving false hope to the victims’ families by withholding valuable information. One undisclosed fact was that Sewol ferry’s structure made it nearly impossible for air pockets to exist in the ferry. Air pockets are cavities within ships that capture oxygen when the ships capsize. Air pockets are a rare phenomenon, but people have survived in sunken ships for days when they were lucky to be trapped in one. In hopes for the non-rescued passengers’ survival, the media, the public, and most of all, the victims’ families prayed for them to be captured in air pockets. Rescue missions were also planned out under the assumption that air pockets existed. However, investigations discovered that the government had deliberately chosen not to share such indispensable information******. Moreover, former President Park Geun-hye’s whereabouts during the 7 hours and 30 minutes of the disaster—from when she was first alerted of the sinking to when she attended the chung-dae-bon******** meeting—is still unknown to this day.

The sinking of the Sewol ferry broke Korean society. Devastated by the hundreds of lives lost and dumbfounded by the government’s irresponsible response, Korea came together demanding justice for the lives that could have been saved with the right instructions. In the years that followed, the Sewol ferry disaster served as a catalyst that righted the wrongs in Korean society, such as the impeachment of President Park. However, the truth about the disaster still lies deep beneath the ocean, and many are still living in a nightmare they cannot escape from.

In the Absence

In remembrance of the waves of pain and sorrow Korea experienced on April 16, 2014, director Yi Seung-jun produced a short documentary chronicling what had really happened on the disastrous day. Earning a nomination for the 92nd Academy Awards’ Best Documentary (Short Subject), the film received critical acclaim for providing a candid and objective narrative on the complex Sewol ferry disaster to foreign audiences. The documentary uses footage from the passengers’ phones and the ferry’s CCTVs, providing a timestamp of what had happened from the first emergency call to when the ferry had completely submerged. Director Yi also included extensive interviews with the parents of deceased students and civilian divers, providing a more raw and personal take on the events that took place on April 16th and the aftermath that followed.

The Yonsei Annals interviewed Director Yi on producing In the Absence and the importance of remembering the Sewol ferry disaster.

Annals: How did you come to produce In the Absence? What inspired you to make this documentary?

Yi: Back in 2017, when Korea’s candlelight protests were receiving attention from foreign media, Field of Vision******* contacted me on creating a documentary that shed light on the protests. I had been talking about the Sewol ferry disaster with my co-producer at the time—about the incredible amount of information that wasn’t released to the public, the pain that the divers and the family of the deceased were living through, and the many problems that weren’t solved regarding the disaster. So, when the offer came, we decided to produce a documentary that explained the relationship between the candlelight protests and the sinking of Sewol ferry. At the time, the Sewol ferry disaster was being used as a political ploy, and some were saying that they have had enough of the disaster, that it was time to move on. But with the pain of the disaster still apparent in our society, we didn’t think that this incident was something to have “enough” of. We thought that the Sewol ferry disaster was something that should ceaselessly be discussed—and that’s how we started In the Absence.

Annals: How did you decide on the title, In the Absence?

Yi: The title came from our main goal of the production—understanding where the pain of the Sewol ferry disaster stemmed from. When the news of the Sewol ferry hit the headlines in 2014, so many of us, the Korean citizens, were heartbroken. Korean society was united in the grief and confusion they were feeling.

At that point, I thought, “we must go back to the very beginning.” I believed that if we returned to the starting point of the Sewol ferry incident, we’d be able to identify the cause of the pain that is still haunting so many lives. So, I started asking questions: What happened during the two hours that the ship sank? What conversations were exchanged? Why did these actions and words bring about so much pain? Looking at these questions, I realized that the ill-functioning government was the cause of this disaster. A country’s government has the responsibility to protect and rescue its citizens, but the government was “absent” when its people needed it the most—thus In the Absence.

Annals: What message did you want to convey through In the Absence?

Yi: I wanted to convey to the audience that people are still hurting from the Sewol ferry disaster, and that we need to understand their pain and stand together because that’s what matters. As time passed, the disaster was being remembered as a “disgraceful event” that exposed the government’s nonfunctioning systems. In response, the government tried to minimize this “scandal” using money to compensate the victims for their loss and pain. I disagreed with this negative sentiment. I believed that the Sewol ferry disaster is neither about money nor disgrace, but about the emotions the divers and the families were feeling, and how Korean society could console them. I also wanted to explain the ways in which the government and our society had failed to comfort the victims. Ultimately, I hoped that people could grasp the victims’ raw emotions.

Annals: When were you most heartbroken during the production process?

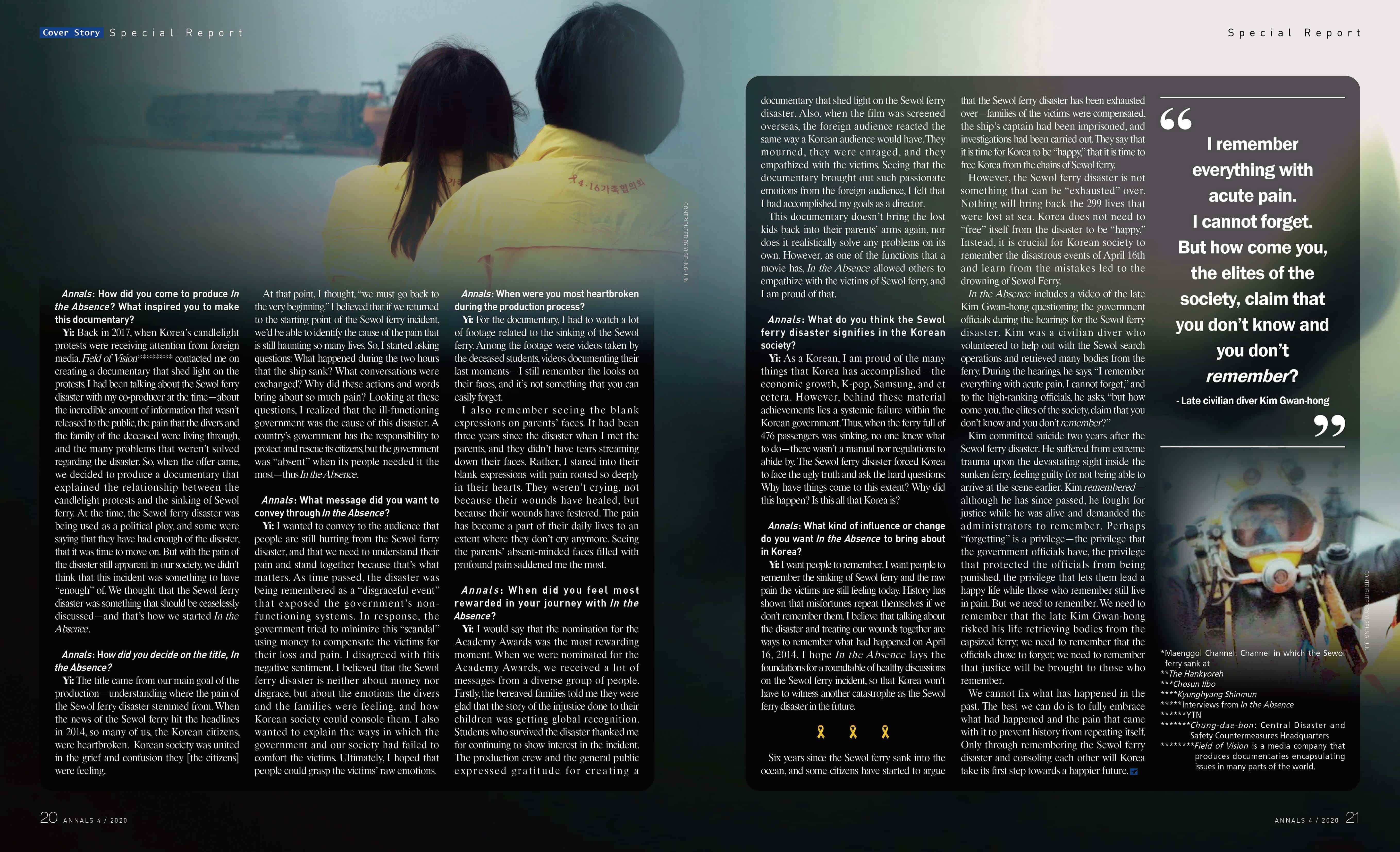

Yi: For the documentary, I had to watch a lot of footage related to the sinking of the Sewol ferry. Among the footage were videos taken by the deceased students, videos documenting their last moments—I still remember the looks on their faces, and it’s not something that you can easily forget.

I also remember seeing the blank expressions on parents’ faces. It had been three years since the disaster when I met the parents, and they didn’t have tears streaming down their faces. Rather, I stared into their blank expressions with pain rooted so deeply in their hearts. They weren’t crying, not because their wounds have healed, but because their wounds have festered. The pain has become a part of their daily lives to an extent where they don’t cry anymore. Seeing the parents’ absentminded faces filled with profound pain saddened me the most.

Annals: When did you feel most rewarded in your journey with In the Absence?

Yi: I would say that the nomination for the Academy Awards was the most rewarding moment. When we were nominated for the Academy Awards, we received a lot of messages from a diverse group of people. Firstly, the bereaved families told me they were glad that the story of the injustice done to their children was getting global recognition. Students who survived the disaster thanked me for continuing to show interest in the incident. The production crew and the general public expressed gratitude for creating a documentary that shed light on the Sewol ferry disaster. Also, when the film was screened overseas, the foreign audience reacted the same way a Korean audience would have. They mourned, they were enraged, and they empathized with the victims. Seeing that the documentary brought out such passionate emotions from the foreign audience, I felt that I had accomplished my goals as a director.

This documentary doesn’t bring the lost kids back into their parents arms again, nor does it realistically solve any problems on its own. However, as one of the functions that a movie has, In the Absence allowed for others to empathize with the victims of Sewol ferry, and I am proud of that.

Annals: What do you think the Sewol ferry disaster signifies in the Korean society?

Yi: As a Korean, I am proud of the many things that Korea has accomplished—the economic growth, K-pop, Samsung, and et cetera. However, behind these material achievements lies a systemic failure within the Korean government. Thus, when the ferry full of 476 passengers was sinking, no one knew what to do—there wasn’t a manual nor regulations to abide by. The Sewol ferry disaster forced Korea to face the ugly truth and ask the hard questions: Why have things come to this extent? Why did this happen? Is this all that Korea is?

Annals: What kind of influence or change do you want In the Absence to bring about in Korea?

Yi: I want people to remember. I want people to remember the sinking of Sewol ferry and the raw pain the victims are still feeling today. History has shown that misfortunes repeat themselves if we don’t remember them. I believe that talking about the disaster and treating our wounds together are ways to remember what had happened on April 16, 2014. I hope In the Absence lays the foundations for a roundtable of healthy discussions on the Sewol ferry incident, so that Korea won’t have to witness another catastrophe as the Sewol ferry disaster in the future.

* * *

Six years since the Sewol ferry sank into the ocean, and some citizens have started to argue that the Sewol ferry disaster has been exhausted over—families of the victims were compensated, the ship’s captain has been imprisoned, and investigations had been carried out. They say that it is time for Korea to be “happy,” that it is time to free Korea from the chains of Sewol ferry.

However, the Sewol ferry disaster is not something that can be “exhausted” over. Nothing will bring back the 299 lives that were lost at sea. Korea does not need to “free” itself from the disaster to be “happy.” Instead, it is crucial for Korean society to remember the disastrous events of April 16th and learn from the mistakes led to the drowning of Sewol Ferry.

In the Absence includes a video of the late Kim Gwan-hong questioning the government officials during the hearings for the Sewol ferry disaster. Kim was a civilian diver who volunteered to help out with the Sewol search operations and retrieved many bodies from the ferry. During the hearings, he says, “I remember everything with acute pain. I cannot forget,” and to the high-ranking officials, he asks, “but how come you, the elites of the society, claim that you don’t know and you don’t remember?”

Kim committed suicide two years after the Sewol ferry disaster. He suffered from extreme trauma upon the devastating sight inside the sunken ferry, feeling guilty for not being able to arrive at the scene earlier. Kim remembered—although he has since passed, he fought for justice while he was alive and demanded the administrators to remember. Perhaps “forgetting” is a privilege—the privilege that the government officials have, the privilege that protected the officials from being punished, the privilege that lets them lead a happy life while those who remember still live in pain. But we need to remember. We need to remember that the late Kim Gwan-hong risked his life retrieving bodies from the capsized ferry; we need to remember that the officials chose to forget; we need to remember that justice will be brought to those who remember.

We cannot fix what has happened in the past. The best we can do is to fully embrace what had happened and the pain that came with it to prevent history from repeating itself. Only through remembering the Sewol ferry disaster and consoling each other will Korea take its first step towards a happier future.

*Maenggol Channel: channel in which the Sewol ferry sank at

**The Hankyoreh

***Chosun Ilbo

****Kyunghyang Shinmun

*****Interviews from In the Absence

******YTN

******Field of Vision is a media company that produces documentaries encapsulating issues in many parts of the world

********chung-dae-bon: Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters