How a nonchalant middle school student became a spy

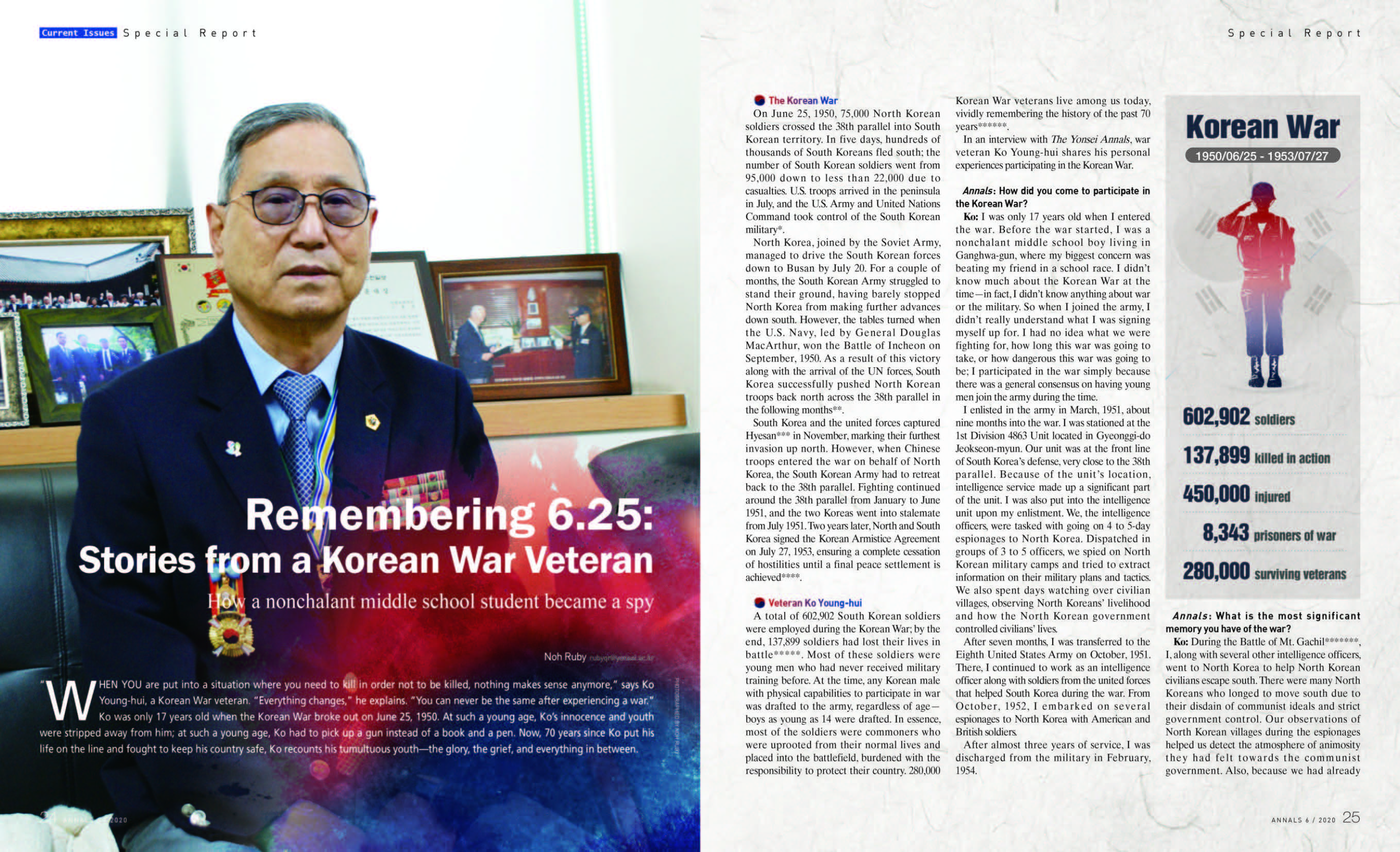

“WHEN YOU are put into a situation where you need to kill in order not to be killed, nothing makes sense anymore,” says Ko Young-hui, a Korean War veteran. “Everything changes,” he explains. “You can never be the same after experiencing a war.” Ko was only 17 years old when the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950. At such a young age, Ko’s innocence and youth were stripped away from him; at such a young age, Ko had to pick up a gun instead of a book and a pen. Now, 70 years since Ko put his life on the line and fought to keep his country safe, Ko recounts his tumultuous youth—the glory, the grief, and everything in between.

The Korean War

On June 25, 1950, 75,000 North Korean soldiers crossed the 38th parallel into South Korean territory. In five days, hundreds of thousands of South Koreans fled south; the number of South Korean soldiers went from 95,000 down to less than 22,000 due to casualties. U.S. troops arrived in the peninsula in July, and the U.S. Army and United Nations Command took control of the South Korean military*.

North Korea, joined by the Soviet Army, managed to drive the South Korean forces down to Busan by July 20. For a couple of months, the South Korean Army struggled to stand their ground, having barely stopped North Korea from making further advances down south. However, the tables turned when the U.S. Navy, led by General Douglas MacArthur, won the Battle of Incheon on September, 1950. As a result of this victory along with the arrival of the UN forces, South Korea successfully pushed North Korean troops back north across the 38th parallel in the following months**.

South Korea and the united forces captured Hyesan*** in November, marking their furthest invasion up north. However, when Chinese troops entered the war on behalf of North Korea, the South Korean Army had to retreat back to the 38th parallel. Fighting continued around the 38th parallel from January to June 1951, and the two Koreas went into stalemate from July 1951. Two years later, North and South Korea signed the Korean Armistice Agreement on July 27, 1953, ensuring a complete cessation of hostilities until a final peace settlement is achieved****.

Veteran Ko Young-hui

A total of 602,902 South Korean soldiers were employed during the Korean War; by the end, 137,899 soldiers had lost their lives in battle*****. Most of these soldiers were young men who had never received military training before. At the time, any Korean male with physical capabilities to participate in a war was drafted to the army, regardless of age—boys as young as 14 were drafted. In essence, most of the soldiers were commoners who were uprooted from their normal lives and placed into the battlefield, burdened with the responsibility to protect their country. 280,000 Korean War veterans live among us today, vividly remembering the history of the past 70 years******.

In an interview with The Yonsei Annals, war veteran Ko Young-hui shares his personal experiences participating in the Korean War.

Annals: How did you come to participate in the Korean War?

Ko: I was only 17 years old when I entered the war. Before the war started, I was a nonchalant middle school boy living in Ganghwa-gun, where my biggest concern was beating my friend in a school race. I didn’t know much about the Korean War at the time—in fact, I didn’t know anything about war or the military. So when I joined the army, I didn’t really understand what I was signing myself up for. I had no idea what we were fighting for, how long this war was going to take, or how dangerous this war was going to be; I participated in the war simply because there was a general consensus on having young men join the army during the time.

I enlisted in the army in March, 1951, about nine months into the war. I was stationed at the 1st Division 4863 Unit located in Gyeonggi-do Jeokseon-myun. Our unit was at the front line of South Korea’s defense, very close to the 38th parallel. Because of the unit’s location, intelligence service made up a significant part of the unit. I was also put into the intelligence unit upon my enlistment. We, the intelligence officers, were tasked with going on 4 to 5-day espionages to North Korea. Dispatched in groups of 3 to 5 officers, we spied on North Korean military camps and tried to extract information on their military plans and tactics. We also spent days watching over civilian villages, observing North Koreans’ livelihood and how the North Korean government controlled civilians’ lives.

After seven months, I was transferred to the Eighth United States Army on October, 1951. There, I continued to work as an intelligence officer along with soldiers from the united forces that helped South Korea during the war. Starting in October, 1952, I embarked on several espionages to North Korea with American and British soldiers.

After almost three years of service, I was discharged from the military in February, 1954.

Annals: What is the most significant memory you have of the war?

Ko: During the Battle of Mt. Gachil*******, I, along with several other intelligence officers, went to North Korea to help North Korean civilians escape south. There were many North Koreans who longed to move south due to their disdain of communist ideals and strict government control. Our observations of North Korean villages during the espionages helped us detect the atmosphere of animosity they had felt towards the communist government. Also, because we had already familiarized ourselves with the geography of several North Korean villages, we were able to help about a dozen North Koreans escape when the battle broke out.

I still remember the cold water wrapping around my legs when we crossed the Imjin River on a pitch-black night. We knew that most of the North Korean forces were far away down at Mt. Gachil during the time of the escape, but having a dozen civilians to take care of made the espionage the most dangerous and harrowing experience I had during my service. We managed to get all the North Korean civilians to safety down south, but I wasn’t able to recover from extreme anxiety for a very long time.

Another very memorable experience I had while spying in North Korea was watching female soldiers train in Mt. Osung. Mt. Osung is one of the highest mountains in North Korea, located very near the 38th parallel. During one of the espionages, me and my team heard gunshots near our shelter in Mt. Osung. Upon hearing the gunshots, we immediately assumed that we were about to be captured by North Korean soldiers. But when we looked out, we were surprised to find hundreds of female soldiers training at an abandoned school nearby. There were female soldiers in South Korea as well, but their main duties were nursing the wounded. The women we found at Mt. Osung, however, were skilled soldiers training with ammunition. Discovering the female troops made me realize how determined the North Korean government was about winning the war. Especially because we came across this troop when South Korea was close to losing the war, it made me think that with this type of determination, North Korea could really win the war.

Annals: What is the most heart aching memory you have of the war?

Ko: I was most devastated whenever my peers failed to return from their espionages to the North. At the time, it was common for only 1 to 2 soldiers to return from a dispatch of 5 soldiers. If they didn’t return by the sixth day of departure, we assumed that they either died or were captured by the North Korean Army. About 40 soldiers were stationed with me in in the intelligence unit at the 1st Division 4863 Unit in March, 1951. However, by the time I moved to the Eighth United States Army, no more than 12 soldiers were left in the unit.

Because so many of my comrades failed to come back to base, I dreaded the day of their return more than the day of their dispatch. When soldiers didn’t return on their designated days, no one would shed a tear even though everyone was filled with anguish and sorrow. As we were constantly consumed with extreme levels of anxiety and tension, oftentimes we couldn’t properly process the grief of losing one of our own.

Looking back, it’s horrifying how teenagers—not even adults—were put through these extreme levels of psychological duress. To lose one’s life at such a young age and to witness your friends die, while being constantly reminded that you could be next, is something no one should experience. My heart aches at the fact that I, along with many other young men, were robbed of our innocence and youth due to the war.

Annals: Did you ever consider desertion during the war?

Ko: I think everyone has considered running away at some point during the war. For me, I genuinely considered leaving the army during one of my espionages. In the beginning of the war, North Korea enjoyed better economic conditions than South Korea. As a result, whenever I spied on North Korean villages, I saw North Koreans living in bigger houses, eating more food, and enjoying higher standards of living. At the same time, the South Korean Army ingrained in us soldiers that communism must be defeated as it will lead to the destruction of Korea. I was trained to believe that democracy and capitalism were the only and the right ways to govern Korea. So when I witnessed North Koreans—under a communist regime—living in better conditions, I realized that what I had believed to be right might actually be wrong.

I fought in the war driven by the belief that my family would be better off living in a democratic and capitalist society. However, upon witnessing wealthy North Korean villages, I started to question whether South Korean ideals were truly correct. Everything I had thought to be right seemed wrong, and at that point I lost the reason behind fighting for South Korea. Living through 70 years since the Korean War, I’m glad I stayed in the South as history has proved democracy and capitalism to be more successful than communism. However, all I wanted to do back then was to flee the army, find my family, and go deep into the countryside where the war wouldn’t affect us.

Annals: As a veteran of the Korean War, how do you feel about the current relationship between the North and South Koreas?

Ko: I’m heartbroken to see that the two Koreas haven’t been unified in the past 70 years since the war. Korea needs to be reunified. North and South Koreans aren’t different people; less than a hundred years ago, people from Hamgyong-do could travel to Jeolla-do without any restrictions. To this day, we speak the same language, enjoy the same culture, and share the same history. It’s a tragedy to see a homogenous nation be divided by political ideals. As time passes, animosity between the two countries grows while the emotional connection between the countries weakens. Before it’s too late, we need to remind ourselves that we are of one nation—North and South Korea must be reunified.

Annals: As a veteran of the Korean War, what do you hope for the future generations of Korea?

Ko: The younger and the future generations of Korea have not, and probably will not, experience the struggles that my generation had gone through. I am more than grateful that the pain of war and chaos ended with my generation. However, I fear that the younger generations lack understanding of the horrors of war. I sometimes hear people make insensitive remarks about wars, saying that it won’t matter if a second Korean War breaks out since South Korea will win anyway. What they don’t understand, however, is that the process of wars is as critical as is the result of wars. Regardless of the result of the war, thousands upon thousands of innocent lives will be taken away. Regardless of the result, you will be forced to shoot point blank at someone because if you don’t, you’ll be the one taking the bullet. Regardless of the result, the horror and trauma of the war will haunt you for the rest of your life. Victory will not and cannot account for the harm that’s been done throughout the course of the war. Thus, whenever I hear the younger generation make these statements, I worry about their awareness of wars. I sincerely hope that the younger generation will change their minds and work to avoid any and all wars in the future.

Lastly, I hope for the future generations to strive for the reunification of Korea. The younger the people are, the less desire they have for reunification. I understand their point of view; they were born into an already separated Korea that enjoys high standards of living. They don’t feel the need for reunification because they don’t know what a unified Korea looks like. But I sincerely hope that the future generations will realize the importance of reunification for our country as a whole. I hope for the future generations to live in Korea—not North or South Korea, but simply Korea.

* * *

Towards the end of the interview, Ko talked about his current life, 70 years since the Korean War. “I don’t think Korean War veterans are given the appreciation we deserve,” he said. Korean War veterans receive around ₩400,000 per month as compensation fees********. Since many veterans suffer from physical and psychological disabilities from the war, they struggle to find a stable source of income. As a result, veterans rely on compensation fees for their livelihoods, and ₩400,000 per month is far from enough. “I remember reading an article about a veteran who stole tangerines for his sick wife because he didn’t have the money to buy them,” Ko said. “Is this how veterans’ livelihoods should be after having put our lives on the line for the country?” he asked.

However, Ko said that it isn’t the small amount compensation that upset him the most. “As time passes, people are forgetting the sacrifices we’ve made to keep the country safe,” he said. Ko claimed that he understands that memory withers with time, but he feels that South Korea isn’t making an effort to remember the war. “The Korean War is recent history; many who experienced the war still make up a significant part of the South Korean population today,” he said. “However, Korea seems so focused on the future right now that the past is being neglected.” Ko said that South Korea needs to reflect upon its past, as understanding and remembering a country’s history is crucial for the country in moving forward into the future.

South Korea has come a long way since the Korean War. For 70 years, Korea has worked ceaselessly in hopes for a better future. As a result of hard work and determination, South Koreans now enjoy high standards of living that seemed impossible decades ago. However, as Ko explained, perhaps it is time for Korea to take the focus off the future and reflect on the history that placed Korea at its current position. Perhaps it is time for South Korea to look back in history and appreciate those who have sacrificed their lives to protect the country from harm.

*History

** Encyclopædia Britannica

***Hyesan: City in North Korea located next to the Chinese border

****Korean War Armistice Agreement

*****National Archives of Korea

******Statistics Korea

*******Battle of Mt. Gachil: Battle between North and South Korean forces from September to October 1951; Located in Gangwon-do, Mt. Gachil was a crucial point of South Korean defense.

********Yonhap News Agency