An insight into Korea’s military culture

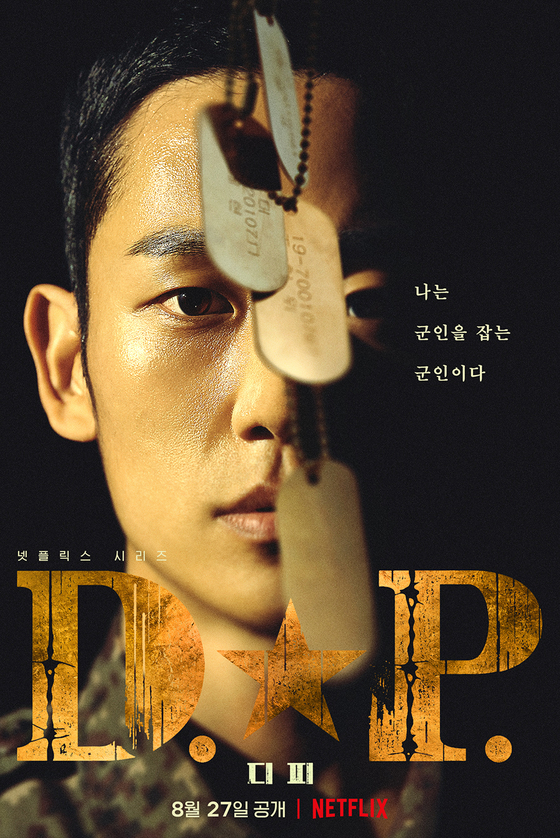

JUST TWO days after its release, the Korean Netflix series D.P. topped the domestic Netflix charts. Released last August, the drama follows the story of Ahn Jun-ho, a soldier who is transferred to the deserter pursuit (D.P.) squad. As a D.P. soldier, Jun-ho works with Sergeant Park Beom-gu and Corporal Han Ho-yeol to catch deserters. Korean men have spoken about how D.P. is a raw and truthful depiction of what the bullying culture was like in the military around 2014[1], and how the show raised public awareness of outdated military customs.

The reason behind D.P.’s domestic success

D.P. was able to gain immense traction due to its portrayal of a lesser-known part of the military—the D.P. Before the release of D.P., civilians were only roughly aware of what the military lifestyle was like through entertainment programs such as Real Men which showcased celebrities following a soldier’s training routine. Yet, entertainment shows like these cannot effectively depict the various duties soldiers of different ranks carry out. In this way, the freedoms that come with a D.P. soldier’s job was a unique premise for a military-centered drama. Jun-ho and Ho-yeol, who is the D.P. leader, often camp out at internet cafes to carry out their search. Soldiers have only recently been allowed to use their cellphones. In 2014, access to technology as a soldier was a luxury. D.P. soldiers were given cellphones to aid in their search, and they did not need to shave their hair and could wear casual clothing for their missions unlike other soldiers. While these D.P soldiers get the benefit of these added luxuries, D.P. revealed how the position exposed soldiers to the dark side of the military.

Cho Seok-bong, Private Yoon, and Sergeant Lim

While each episode focuses on different deserters’ stories, the final few episodes follow the story of private Cho Seok-bong, an ex-Judoka turned art teacher. Seok-bong’s character is fundamental to D.P.’s plot as it depicts that regardless of someone’s physique or physical ability, they are still susceptible to psychological victimization. When Seok-bong enters the military, he becomes the target of his senior Hwang Jang-soo, a notorious bully, and suffers severe mental and physical bullying. Unfortunately, Seok-bong is later seen mistreating his junior soldiers as he was calling them out at night and abusing them, to which Jun-ho tries to stop him saying, “stop, we also got beaten up a lot.” However, Seok-bong replies, “you didn’t even get beat up much since you weren’t around doing your D.P. stuff.” This scene marks a key change in Seok-bong’s character, as he becomes cruel and aggressive—a foil of his nickname bong-di-ssaem that represents his kind personality.

The intense bullying that Seok-bong undergoes is inspired by the 2014 Private Yoon case, which revealed the strict hierarchical military culture in Korea. Twenty-year-old private Yoon was beaten every day until he was killed and pronounced dead on April 7, 2014. The soldiers’ abusive acts toward Yoon included forcing him to consume toothpaste, making him lick their spit off the floor, applying antiphlamine—a lotion used to relieve muscle pain—to his genitals to humiliate him, and much more. The day Yoon passed, he fell unconscious while choking on food, according to the Center for Military Human Rights[2]. However, it was later found that Yoon’s choking was not an unfortunate coincidence, but a result of the harsh beating inflicted by other soldiers. Investigative files later revealed that Yoon had been the target of a toxic military culture that had predated his enlistment—privates before him were treated maliciously by Sergeant Lee, the main perpetrator behind the case, who then reciprocated those abusive actions onto the newcomer, Private Yoon.

Merely two months later, Sergeant Lim from a different unit, who claimed to have been seriously bullied, went on a shooting rampage that killed five soldiers. Shortly after the Sergeant Lim case, a civilian stated in an interview with SBS, “Private Yoon if you can endure it, Sergeant Lim if you can’t[3]” which has since become a proverb for the issues plaguing the Korean military. The aforementioned case is represented in D.P.’s post-credit scene when Kim Ru-ree, a soldier from another camp, shoots his comrades.

Words from a former D.P. soldier

The Yonsei Annals spoke to Oh Geun, a former D.P. soldier who joined the military as a 241st non-commissioned officer in the navy and was discharged as a sergeant in 2021. Oh found the first episode of D.P. most striking, where a defector committed suicide using the lighter that Jun-ho, the newly dispatched D.P., gave him. Oh claimed that the scene clearly touched on the “painful situations defectors go through” and “the dire consequences of when a D.P. squad decides to play hooky instead of staying focused on their search.”

Oh said that following the Private Yoon and Sergeant Lim incident, his military unit conducted “counselling with interested soldiers” on bullying-related matters, and also ensured that the firearms were kept safe according to procedures. As such, contrary to what the Korean military culture looked like back in 2014, Oh believes that the conditions have “improved a lot” over the years, especially through holding regular accident prevention education sessions in the army. According to Oh, these sessions teach soldiers “the consequences of their actions,” as their punishments are documented in their criminal records even after they are discharged. Oh also commented how the military used to have a “vertical culture” during his primary years, referring to how soldiers had to listen to the demands of their senior officers regardless of their own judgements. Oh believes that today’s military has shifted to a “horizontal culture” where individualism, open expression of opinions, and relationships are emphasized. Oh shared that for abuse within Korean militaries to improve, the treatment of soldiers should be changed first—“if the military’s treatment improves, the current absurdity will alleviate.” However, the military’s efforts seem questionable with 37 suicide cases being reported between January and June this year, which is just a few figures below last year’s amassed 40 cases[4].

The impact of D.P.?

On September 9, the Ministry announced that the tasks of D.P. soldiers would be handled by officers starting next year[5]. This announcement startled the public, as its timing was uncanny with the release of the show. In the previous Military Court Act, soldiers were included in the Military Law Police Department, which assisted investigations under orders from military prosecutors or executive officers. Many people thought that the timing of this law change was influenced by the drama. However, the military noted that the abolition of the D.P. squad is not related to the popularity of the show[6]. They also emphasized that the situation portrayed in the drama is far different from what the Korean military looks like today. Statistics showed that the military service defections decreased by nearly 30% between 2019 and 2020[7].

* * *

Following D.P.’s release, public figures have spoken on the issue of Korea’s outdated military culture and how reformation has been long overdue. For example, actor Ha Seok-jin revealed that he was a victim of a senior like the character Jang-soo during his military service[8]. As such, D.P.’s success was not only due to its plot revolving around a lesser-known role within the military, but because its dark depiction of military life mirrored real issues. While some just enjoy the violence and sensational plot of the show, it has also raised concerns about how the military will continue to make efforts to improve its environment.

[1] Global Economics

[2] Pulse News

[3] SBS

[4] MBC News

[5] Yonhap News

[6] Yonhap News

[7] MBC News

[8] Chosun Ilbo